Catholic Schools Go Charter to Survive

Paul Stephens | Jul 30, 2009 | Comments 9

By Paul Stephens with additional reporting by Elaine Meyer

A student at a the Trinidad Campus of Center City Public Charter Schools passes by part of the school's mission statement. Secular values have replaced the religious curriculum since the school became public last year.

Every morning, students at the Trinidad campus of Center City Public Charter Schools in Washington, D.C., line up on the pavement outside the school — girls in plaid jumpers, boys in navy slacks and white shirts. Hands on their chests, they recite the school’s mission:

The Center City Public Charter Schools empower our children for success through a rigorous academic program and strong character education while challenging students to pursue personal excellence in character, conduct and scholarship in order to develop the skills necessary to both serve and lead others in the 21st century.

It’s not the Lord’s Prayer, but it will have to do. Decidedly devoid of godliness, the children’s chant is an attempt by the school to replace one element of the religious education it used to impart. Trinidad is one of seven financially-troubled Catholic schools in the District of Columbia that converted to charter schools last fall in order to save them from being permanently shuttered.

The price for losing its religion is complicated. On one hand, the charter structure brought with it several thousand dollars more per student than the Archdiocese of Washington was able to provide, and it offered a guaranteed place for Holy Name’s former students and teachers.

Audio slide show: Losing their religion. Look inside to see how the conversion has affected the school.

“We have a lot more resources than we’ve ever had before,” said Mary Anne Stanton, who oversaw the schools as the executive director of the Center City Consortium, a group of 13 Catholic schools in the district with a central administration and shared resources. “We were coming from starvation,” she said.

But some parents and Catholic educators pause to ponder the loss to Catholicism, and the loss to the spiritual life of the children, which the schools provided for nearly a century. To them, the schools were saved, but their souls were lost.

“The thing that made Holy Name special was the name,” said Charles Noble, a grandfather of pre-kindergarten student at the Trinidad campus, a graduate of Holy Name and a former teacher at the school. The name signified, he said, what really made it special: its Catholicism.

Now he worries that the school may become “just another charter school.”

Along with its name, Trinidad purged itself of its religious elements. A stone cross still stands over the building’s front entrance, but all the crucifixes have been removed from the interior walls. Morning prayer has become morning meeting. The few nuns who work at the school still dispense advice, but it is no longer the catechism. A statue of the Virgin Mary has been replaced with a shrine to the school’s rather lengthy core values: collaboration, compassion, curiosity, discipline, integrity, justice, knowledge, peacemaking, perseverance and respect.

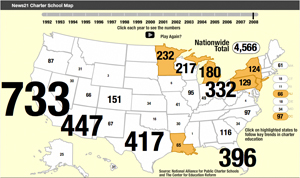

The District of Columbia’s experiment in wholesale conversions may have a huge impact on the charter-school movement and urban Catholic schools across the country. There are signs that other cities and archdioceses around the nation are taking their cues from the so-called success in D.C., in an effort to save high-performing urban Catholic schools struggling with funding. Eight Catholic schools in Miami will be replaced by charter schools this fall, and four Catholic schools in Brooklyn, N.Y., have discussed the possibility of conversion, though only one school has applied to the state charter board for approval of its charter. “Going charter” has also been discussed by the dioceses in San Antonio, San Diego and Chicago.

The full effect on urban Catholic schools of the nation’s recent proliferation of charter schools is yet to be seen. While charter laws may provide financially-strapped dioceses an exit strategy for their religious schools, it also creates a new educational marketplace. And in some areas of the country, Catholic schools that are still Catholic are beginning to be forced to compete for students against new charter schools — the charter option now attracting attention far and wide.

Photos: Keeping the faith. Inside a D.C. Catholic school that has stayed a religious school, despite the challenges.

More than 1,400 Catholic schools have closed in the United States since 2000, 17 percent of that year’s total, according to the National Catholic Educational Association. Enrollment has decreased by a similar percentage: More than 460,000 students have left Catholic schools in the past 10 years.

The loss of students from Catholic schools can be attributed largely to the demographic shifts that have taken place in American cities and the Church since the 1960s, as many Catholic families left the city for the suburbs and the number of Catholic clergy declined. (The Catholic schools in D.C. have served a mostly black, non-Catholic population for several decades.) Recently, however, charter schools may have also played a role in drawing students away.

“Anybody with three or four brain cells to rub together knows that charter schools have had an effect on Catholic schools, and it hasn’t always been positive,” said Stanton, even as she defended the conversion of her schools as the only reasonable alternative to their closure.

Across the nation, it is difficult to put a number on how many students Catholic schools have lost to new charter schools in their districts, since dioceses do not track where students who leave their schools have gone. Anecdotal evidence, though, points to the idea that charter schools are drawing some of their populations away from Catholic schools. And the competition seems obvious: When charter schools are offering for free the academic and disciplinary environment of Catholic schools, some of the mostly non-Catholic population of those areas would likely choose charters.

Timeline: A History of Catholic Schools. Explore the history of how and why the Catholic parochial system developed in America.

“I can’t tell you how many people come up to me and say ‘KIPP is the new Catholic School,’” said Scott Hamilton, one of the early developers of the Knowledge Is Power Program, a nationwide chain of charter schools known for running high-performing schools in traditionally low-performing, low-income, minority neighborhoods. In many ways, KIPP provides the alternative to traditional public schools that was once only provided by Catholic schools in those neighborhoods: an environment of strict discipline, a focus on academic success, a strong school culture, and a values-based curriculum. Many charters have emulated KIPP’s “no excuses” model, which the founders freely admit was based in part on the Catholic model.

When Center City Public Charter Schools opened the doors of its seven schools in the D.C. area last fall, the school buildings themselves were not new, but many details inside them were. The total student population of the schools had swelled from about 1,100 to over 1,400, and about 60 percent of students were new. The teachers who stayed on through the conversion received a 35 percent raise. The seemingly generous per-pupil funding that school received from the city (over $11,000, compared to the approximately $7,500 per pupil that the Archdiocese had spent) meant more music and arts, special education counselors, and programs for students who do not speak English. Many of the schools added pre-kindergarten programs. For the first time in a long time, school administrators did not have to worry about whether the schools would be able to survive financially through the next school year.

Now relatively flush with resources, the Center City schools make up the largest charter management organization in the district. The schools’ test scores will be closely examined to see how they compare with pre-conversion performance, but the conversion itself was a remarkable feat. Seven schools serving pre-kindergarten through eighth grades became public schools almost overnight. Schools that would certainly have been closed are now thriving and serving more students from the neighborhoods where they are located. And the new students are generally poorer. When the schools were Catholic, about 45 percent of kids came from outside the city, but now a large proportion of the kids walk to school, Stanton said. “In some was we’re doing what we always wanted to do which is to serve these neighborhoods,” she said.

That the schools were saved from certain death is undeniable, but that is cold comfort to those who believe that Catholic schools are at risk of dying out in the inner city.

Juana Brown, the head of schools at Center City, compared the choice to go charter to the biblical story of the judgment of King Solomon. Torn between their religious and educational missions, yet intent on saving the schools, the schools had to give one goal up — even if it meant giving up something as important as religious education.

Standing in the hallway waiting for his grandson to finish a new after-school program, Noble recalled the way kids used to interact with Holy Name’s parish priest and ask to pray with their teachers or one of two nuns who worked at the school. When tragedy befell the school community, he said, they could come together in prayer to recover.

Noble said that the schools seem to have more resources now, and that parents also seem to be making fewer sacrifices to send their kids to the school, but he also thought that something had been lost.

“Parents really did some things to keep their kids here,” he said, shaking his head and falling silent for a moment, as if remembering a specific example too heartbreaking to repeat. “They really did believe in a Catholic education.”

Filed Under: Featured • Reshaping Communities • Washington, D.C.

About the Author:

My English is not good, not too much to see to understand. But thank you to share with me

The Lord is good worship him!

Ah! What a pleasure to have you faithful readers who postent small comments …

Hey darling, sweet site! I really appreciate this blog post.. I was curious about this for a while now. This cleared a lot up for me! Do you have a rss feed that I can add?

Hi there, nice site with good info. I really like coming back here often. There’s only one thing that annoys me and that is the misfunctioning of comment posting. I usually get to 500 error page, and have to do the post twice.

Just want to say your article is striking. The clarity in your post is simply striking and i can take for granted you are an expert on this subject. Well with your permission allow me to grab your rss feed to keep up to date with forthcoming post. Thanks a million and please keep up the ac complished work. Excuse my poor English. English is not my mother tongue.

Hi!

Usually when i see a blog i read through it and move on, however this one was trully a good 1, i thought i would take the time to give you thanx for such a delightful blog post.

[...] Explore the history of how and why the Catholic parochial system developed in America. Back to main story. [...]

[...] Produced by Paul Stephens and Elaine Meyer Holy Name, a financially troubled Catholic school in Washington D.C., became the Trinidad campus of Center City Public Charter Schools last year. The school shed its religious curriculum in order to stay open. Back to main story. [...]