Is Profit Dead?

Sharon McCloskey | Jul 30, 2009 | Comments 4

By Sharon McCloskey, with reporting and media production by Annie Hauser and Michele Hoos

For-profit companies rushed into the public school market at the same time the first charter schools took hold. Some 17 years later, can we safely say that this profit experiment has run its course? Or has it simply moved out of brick and mortar buildings and into cyber space?

(PHOTO: AP)

When Chris Whittle announced the formation of Edison Schools in 1992, he was betting on a startling, simple proposition: that corporate America, hewn to a bottom line of efficiency and profitability, could do a far better job running the public schools than did local school districts. It was a smart idea with a noble touch: Fix the schools and make some money.

Whittle succeeded for a time, enough so that the company went public in 1999, but next came a series of missteps and mishaps that sent investors heading for the hills. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission was scrutinizing its financials and regulators were challenging its test scores and school performance. In 2003, a group led by then-Florida Gov. Jeb Bush took the company private, and Edison Schools became the poster child for the failure of the for-profit education management model.

But Edison Schools did not die. The company kicked around quietly for a few years, held on to a few school management contracts and searched for greener pastures. In 2008, the company acquired Provost Systems, an education software company, reconfigured itself as Edison Learning, and announced a new focus on delivering online and supplemental education services.

“We envision a brighter future liberated by the power of technology and the Internet,” Edison C.E.O. Terry L. Stecz proclaimed in his letter announcing the change to investors and employees.

Edison’s recent transformation reflects yet another chapter opening in the tale of the education management business. Even though doubts lingered following the Edison Schools debacle, for-profit education management have grown steadily over the years. Indeed, reports of the death of education management organizations (E.M.O.s) have been greatly exaggerated. They are alive and thriving in a new realm: cyberspace.

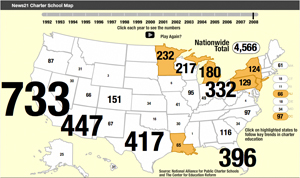

Most charter schools continue to be managed by their founders, but the number using E.M.O.s is growing and is now at 22 percent, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. More companies are launching into cyberspace, even though many remain wary of online classrooms and skeptical of their academic results.

Gary Miron, a research scholar from Western Michigan University, has been tracking E.M.O. growth for the past 10 years. During that period, says Miron, the number of for-profit E.M.O.s has grown from 14 in 1999 to 50 in 2008, and the number of schools served by those E.M.O.s rose from 131 to 533.

But as he compiles his latest report with colleague Jessica Urschel, and Alex Molnar from Arizona State, Miron is seeing a new trend. “For-profit growth (in terms of number of companies) appears to be leveling off, and the expansion we’re seeing now is in the nonprofit sector,” Miron said.

Though still confirming numbers for the report due out in September 2009, Miron estimates that the number of schools managed by for-profit companies declined from 533 to 525 over the past year, while the number of nonprofit-managed schools increased from 488 to 622. This is due, in part, to the decrease in number of schools managed by Edison — from 80 to 62 over this past year, affecting the for-profit sector — and the rapid growth of KIPP schools on the nonprofit side. KIPP, also known as the Knowledge Is Power Program, had a total of 66 schools in the 2008-2009 school year.

Growth still continues in the for-profit sector, notes Miron, though in a different direction. Like Edison, existing companies appear to be focusing on the diversification of their products and services, instead of on acquiring more schools.

That growth is most notable in the virtual, or online, education sector. Although his group has only collected data on virtual schools since the 2003-2004 school year, “the number of E.M.O.-managed virtual schools has grown from 17 to 40,” said Miron. Virtual schools accounted for only 4 percent of the E.M.O.-managed schools in 2003-2004. In 2008, they accounted for 8 percent.

And while the total number of virtual schools in the overall charter landscape may be small, such schools tend to have much larger enrollments than their brick-and-mortar counterparts. In 2008, 17.4 percent of all students enrolled in E.M.O.-operated schools were in virtual ones.

Making Money Online

Virtual charter schools are leading the education management sector largely because they are proving to be profitable. Lower costs and higher demand are main causes, but the schools also have a certain grassroots appeal.

Virtual learning “can be a democratizing force,” said James Maher, an analyst with the San Francisco - based investment banking firm Think Equity LLC. This is especially true for low income students who might have safety concerns about their local schools and limited access to resources, like computers, at home. Cyberschools provide their students with computers as part of their programs. “Virtual learning allows slower and faster students to work at their own pace, and often in a more secure place,” said Maher.

Terry Moe and John Chubb, who last took on education’s special-interest groups in their 1990 “Politics, Markets and America’s Schools” agree with Maher’s assessment. In their new book, “Liberating Learning,” they portray online schooling as the great equalizer, allowing students and parents to sidestep bureaucracies and unions and get straight to learning.

Not everyone is jumping on the virtual-school bandwagon yet, though, as data establishing academic performance at these schools is inconclusive. In Pennsylvania, for the year ending June, 2008, only three of the state’s 11 virtual schools met required testing proficiency levels.

Maher sees growth in the virtual sector continuing. Obviously, as an outgrowth of distance learning, virtual schools can help in large geographic areas, like Wyoming. But demand is rising elsewhere. Some states are now requiring districts to offer online classes. In Michigan students are now required to take one online course, he said. And Florida now requires all school districts to provide an online school as an educational option.

From a company perspective, online education is also attractive because its platform is so nimble. Online curricula, once designed, can be used over again, be easily tweaked, and, in the event of lost business, be peddled elsewhere. Such curricula can also be sold in bits — Advanced Placement courses, for example - as well as an entire program. Amy Junker, an analyst with Robert W. Baird & Co., agrees with Maher that, going forward, this hybrid development gives education management companies a good chance for success.

Cyber Domination

Two companies continue to lead the virtual-school sector: K12 Inc. and Connections Academy. K12, based out of Herndon, Va., is doing particularly well. The company, launched in 2000 and public as of 2008, may see a 40 percent growth in revenues by year’s end, Junker projects.

K12 recently came out a winner in a battle with the Chicago teachers union, which had challenged the state’s authorization of the Chicago Virtual School District as a “home-based” charter school prohibited under Illinois law. In June, the Cook County Circuit Court dismissed the union’s suit, finding that the virtual school district was subject to the same state regulations as traditional public schools and was not “home-based.”

That battle taught K12 that it would not be immune to problems plaguing its more traditional competitors in the brick-and-mortar sector: unions, funding, accountability, mismanagement and reliance on an unpredictable client base — school districts.

Funding remains the bane of charter-school development, for both E.M.O. and self-managed charter schools. While traditional schools bemoan their lack of public funding, their cyber counterparts may actually get too much. Ironically, what makes them profitable creates a big public-relations problem.

Virtual schools have much lower facility and overhead costs, but they still receive the same funding as the brick-and-mortar schools, leaving many virtual schools with significant fund balances at year’s end.

In states such as Pennsylvania, Ohio and Florida, where virtual schools have a large presence, debates over this funding inequity are reaching the state legislatures, particularly as school districts grapple with budget deficits. In Ohio, Gov. Ted Strickland has proposed cutting funding for online schools from $5,732 per student to $1,500. And as the Pennsylvania Cyber Charter School Board announced an increased budget of almost $90 million for the upcoming school year, critics renewed their pleas for changes in cyberschool funding.

Should the funding equations for cyberschools be adjusted so that their profit margins are narrowed, success for virtual-school E.M.O.s may prove to be as elusive as it has been for the brick-and-mortar sector.

Virtual-school E.M.O.s are also learning that, like their brick-and-mortar competitors, success depends upon the vagaries of an unpredictable client base - school boards. K12 is facing that problem now, as it is embroiled in a battle between one of its largest clients — Pennsylvania’s Agora Cyber Charter School, from whom K12 derives 10 percent of its revenues - and the Pennsylvania Department of Education. In April, the state suspended Agora’s charter after an investigation revealed that its board had contracted out management services to both K12 and a company owned by one of the school’s founders, a violation of the school’s charter. Since then, the state has held all funding for the school in escrow - though K12 has been allowed to pay school expenses from that fund. In turn, the allegedly-improper management company has sued K12 in federal court to recover the money K12 is spending from the fund. While the courts sort out the situation, 10 percent of K12’s revenues hang in the balance, along with Agora Cyber School’s charter.

Raising the Bar

Mosaica Education Inc. is another for-profit slated to jump into the virtual-school realm this September, when it plans to open two online schools in California and Arizona. Mosaica — like Edison — has found itself tiptoeing into cyberspace, forced to reinvent itself in order to survive.

Founded in 1997 by Dawn and Gene Eidelman, Mosaica distinguishes itself from its competitors with its “Paragon” curriculum. Mosaica students spend half the school day learning traditional subjects and the other half immersing themselves in a period of history, like the Renaissance. The curriculum has since been criticized, though, for causing some Mosaica schools to churn out low test scores. A 2003 study of the Paragon curriculum by Howard Nelson of the American Federation of Teachers AFL-CIO discredited Mosaica’s own assessment of student performance and found Mosaica schools ranking below average at all grade levels. Still, Mosaica CEO Michael Connelly stands by Paragon, claiming that it helps students enhance basic skills. “We think our kids do well on basic skills testing because of Paragon,” said Connelly.

Tracking the actual performance of Mosaica schools has always been difficult since its portfolio of schools has been somewhat of a revolving door, with schools leaving the Mosaica fold and new ones entering on a regular basis.

As noted in the Miron report, Mosaica had 36 schools in 2008, after losing seven schools from the prior year. The company’s Web site currently lists 33 schools open in the United States, with five from this past year no longer in the company’s portfolio. Miron, at Western Michigan, says Mosaica has a reputation for a high number of schools leaving its management, either breaking away at the end of the original five-year contract, or severing ties before the contract is up.

Not all Mosaica schools have problems or are looking elsewhere for management services. In Michigan, for example, Mosaica schools in Flint and Pontiac are testing at above-district levels, and staff and parents are happy with Mosaica’s management, especially compared to their public district schools.

The reasons for Mosaica’s erratic growth typify problems plaguing other E.M.O.s — poor performance in some schools, mismanagement in others and overall high management fees. Mosaica charges 10 to 15 percent of a school’s annual revenue.

Like Edison, Mosaica has managed to work around those problems and has demonstrated a chameleon-like ability to reorient itself in the E.M.O. landscape. In 2004 it began to expand internationally, opening schools in the Middle East. Today it operates seven schools in Qatar and Abu Dhabi. And now, with the opening of two virtual schools, it will continue to diversify by stepping into cyberspace.

As they have for years, Edison and Mosaica continue to compete in the brick-and-mortar sector. But now they’ve seen the cyberlight — driven perhaps by the success companies like K12 are now enjoying, or perhaps by the possibility of delivering a quality education to more students.

“Competition drives innovation,” says current Mosaica C.E.O. Michael Connelly. “I’ve been doing this for 12 years, with 18,000 students, and I’ve never had a single parent that cares whether you’re a for-profit, nonprofit, or what you are. All they care about is is their child getting a better education than before.”

Filed Under: Michigan • Unchartered Territory

About the Author:

I have visited your blog before. The more I read, the more I keep coming back! ;~)

I am really interested in this topic can you provide me with any more information on it? Greatly Aprecciate it!

This is a nice blogging platform. What is it called?

This is an interesting blog you have her but I can’t seem to find the RSS subscribe button.