By Maura Walz

The big education story over the weekend was Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of the Diocese of Brooklyn’s announcement of a plan to convert four Catholic schools into publicly-funded charter schools—the first time New York has converted parochial schools into charters.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio of the Diocese of Brooklyn’s announced a plan to convert four Catholic schools into publicly-funded charter schools—the first time New York has converted parochial schools into charters. AP/File

The announcement came less than a week after a panel of journalists and educators convened at Columbia University’s Teachers College to map the dire straits in which New York’s Catholic schools increasingly find themselves. The event was structured around a discussion of writer Patrick McCloskey’s new book, The Street Stops Here, which chronicles a year at Rice High School in East Harlem. The release of McCloskey’s book also coincided almost exactly with the Diocese of Brooklyn’s proposal to shut down 14 elementary schools at the end of this academic year.

All of the panelists started from the assumption that yes, Catholic schools are worth saving. But why? The term “social justice” popped up again and again throughout the conversation. Many Catholic schools teach students in highly disadvantaged areas and provide a low-cost education that, according to panelist Pearl Rock Kane (director of the Klingenstein Center for Independent School Leadership, based at Teachers College), leads to more equitable educational outcomes and far outperforms local public schools. For example, Hunter College professor Joseph Viteritti pointed to the fact that 80 percent of Catholic school students graduate. At Rice High School, profiled in McCloskey’s book, all of the seniors are required to apply to college and over 90 percent of them enter. Columbia Journalism professor Sam Freedman noted that Catholic schools are frequently the first stretch of a path to the middle class for many of their students.

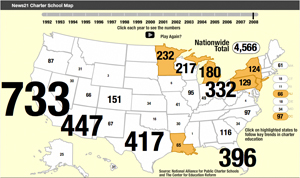

No one on the panel or in the audience seemed to argue that Catholic schools are failing the students they serve. But the most interesting questions came out of some gentle challenges about why Catholic schools are needed for their successful educational model to continue to exist. What will happen, for example, when some of the city’s Catholic schools were converted into publicly funded charter schools? And what elements of the Catholic educational model can be emulated by public schools, where they would have a wider impact? These questions are particularly interesting because, as Vitteritti noted, there is evidence to suggest that the spread of charter schools in urban neighborhoods has had a detrimental effect on the enrollment in Catholic schools.

Viteritti acknowledged that the core values of the schools don’t necessarily need to be religious. But, he said, “to take religion out of religious schools takes away their identity.” McCloskey described the “moral universe” that Catholic schools establish as a way of separating the educational environment from the “street culture.” A religious context isn’t necessary to establish that emphasis on values, he said, but it is easier to do when a religious element is present.

Vitteritti also emphasized the value of Catholic schools in a society that values religious pluralism. And, he said, in many of the poorer communities served by parochial schools, religion is frequently a glue for the communities and that gives Catholic schools a special stature.

There are some elements of the Catholic model of education that can be emulated by public schools, however. Freedman pointed to the strong rejection of the “culture of low expectations.” The requirements that every student apply to college and the resistance to the practice of tracking students, for example, are policies that Freedman said have a great impact on the educational outcomes of Catholic school students that could be replicated easily in public schools.

Freedman also added an interesting side note about the coverage of Catholic education in the New York media. Coverage of Catholic schools frequently slips through the cracks between the religion and education beats, Freedman said, and busy journalists’ attention focuses on public schools because they’re supported by public funds and because of the sheer number of students enrolled in them. (Freedman cited the work of David Gonzalez at the New York Times as an exception.)

Freedman discussed the kinds of stories that journalists write about Catholic schools. “When Catholic schools close, the default position is a sob story,” he said. And while it is in some ways a sob story, he continued, “hard questions also need to be asked.” He listed some of these questions: how do we conceive of social justice questions with regards to Catholic education? What’s the interest of New York’s Catholic population in keeping the schools open? Many heavily Catholic populations (including Irish, Polish, Italian and German groups) are becoming increasingly middle class – where are they and are they supporting the schools? Which Catholic schools are succeeding at fundraising? If they’re not succeeding, why not?

The charter school take-over of Catholic schools, of course, adds a whole new set of questions to the discussion. What elements of the Catholic school culture will the schools carry with them in their new incarnations? What will happen to Catholic school teachers who aren’t certified to teach in public schools? And will this have an impact on the already somewhat competitive relationship between Catholic schools and charters in the same neighborhoods? Washington, D.C. converted seven parochial schools into charters last year and it will be interesting to watch how this plays out in New York.

eating habitswonderful

We suffer over at ours from loads of traffic but very few commenters apart from our own group. Maybe this will help them? Love the blog.

My English is not good, not too much to see to understand. <

Fantastic blogpost, thanks a lot!

Great post. Thanks!

I came across your blog today and am looking forward to reading the archives!

This post resonated so loudly with me