-------------------------------------------

A LOST AND FOUND FOR KIDS

The Tijuana Temporary Shelter for Minors was established as a test case to alleviate the burden of young children who are caught trying to cross into the United States illegally, often smuggled without a family member with the help of a coyote or pollero. Just a few feet from the border line, the 25-foot trailer houses a nursery, a room with two bunk beds, a small office, kitchenette and a sitting room with a TV. The shelter opened in February 2004. Since then, it has processed 11,400 children (65% boys, 35% girls).

It is difficult to estimate how many children are smuggled into the United States, but the Tijuana sector border patrol deports a steady stream of kids every day. During the summer, the number of deported minors nearly doubles due to summer vacation from school. About 80 percent of these children are trying to join family members already in the U.S. The remainder are heading north in hopes of finding a job and a better life.

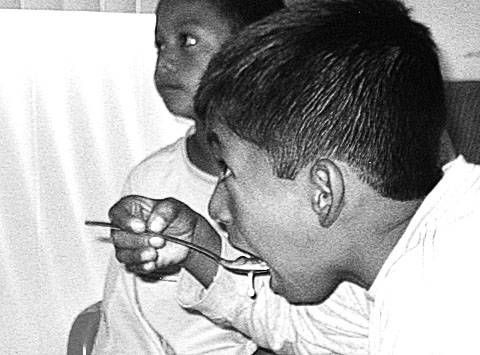

As we watched the faces of the children in the first of two daily vanloads delivered by border patrol, all we could see was fear and bewilderment. The success of the shelter is daunting and almost unbelievable -- unless you spend a day with the three government workers who manage to reunite 85 percent of the children with family members. Armed with only a phone line and the Internet, which they just began using last month, they are able to unite unaccompanied minors with a close relative by 5 PM. The remaining 15% are placed in an overnight shelter, where they are reunited with family members within a week or two.

With kids ranging from seven days to 17 years old, it is difficult to fathom what the process was like before. We asked the director of the center, Enrique Mendez, what life was like before the DIF (Desarrollo Integral de la Familia) trailer. Mendez described the chaos of immigration officials juggling paperwork with diaper changing. Today, the care these frightened children receive as they enter through the gate into Mexico is remarkable. They are provided with food (cold breakfast provided by the federal government), first aid, toys, even a missing belt or shoelace (Department of Homeland Security treats young detainees no differently. They make children remove all these items when detained.) More importantly, they provide children reassurance that they are safe and will be home soon.

Due to this shelter’s proven effectiveness, a few others have sprouted up along the border in other states. With such little resources, this handful of children’s shelters is easing the impact of immigration policies on children torn between two countries.

A MOTHER'S DILEMMA

Ten years ago, Aramida Gramajo made an impossible choice.

You’ve heard Aramida Gramajo’s story before. She’s an illegal immigrant who works for less than minimum wage in Inglewood, California cleaning motel rooms. She barely made it across the blinding desert to cross illegally to Texas. She is a hard-working woman trying to do what’s best for her family and children. You’ve heard this story before.

But have you put yourself in this story? Imagine leaving your five children in Guatemala with your aging parents and traveling 2000 miles to make enough money to support that family.

Leaving her children was a trade off for Aramida. She left to make money but she also left a husband who repeatedly raped her and abused her. Leaving meant she could not be there to protect her children from him. Leaving also meant that they would be able to eat.

According to the 2006 CIA World Factbook, 75% of the population of Guatemala lives below the poverty line, this in comparison to the 12% who live below the poverty line here in the United States. The infant mortality rate in Guatemala is about 30 deaths for every 1000 births and according to data compiled by the World Bank , 23% of children under the age of five are malnourished. The United States’s infant mortality rate is about six deaths for every 1000 babies born.

After paying $4,000 dollars to get to the United States (See: the cost of smuggling) Aramida gave herself 14 days to find a job and get to work.

(Watch Aramida talk about what it was like to leave her children and come to the United States.)

Slowly, with the help of her sister, she was able to gather enough money to bring two of her daughters to America. She paid $4,000 to get her oldest daughter, Christi, over the border, and $5,000 for middle daughter Suli. But Suli’s experience crossing the border was traumatic.

(Watch Aramida talk about her daughter Suli’s trek.)

It’s been almost ten years since she’s seen her other three children, Analucia, Evelyn, and Wilbur, but with the help of a new teleconferencing service called Amigo Latino, she was able to see her children and parents face to face just a few weeks ago.

Ten years is a long time to be away from family, so while the reunion was happy, the emotions of guilt, tears and sadness were also along for the ride.

(Watch Aramida see her family and Wilbur, the child she left when he was a baby, for the first time in almost a decade.)

The teleconference pulled Aramida in multiple directions. She has been unable to send money home recently because she has been paying for Suli to receive therapy to deal with what the abuse she suffered at the hands of her father and the coyote who smuggled her into the U.S. But Aramida promised her mother she would start to send money again. Her mother made it clear that Aramida should not forget about the children who are back in Guatemala.

And Aramida hasn’t forgotten about them. But she does say that after what happened to Suli, she is scared to try to bring anymore children to the U.S.

Near the end of the hour-long experience her elderly father spoke up to say goodbye. He imparted fatherly wisdom on Aramida and Suli as they sat quietly listening with tears rolling down their faces. They all knew that this would most likely be the last time they would see him alive.

After the teleconference Aramida expressed the frustration and conflicting emotions many women in her position must feel: a desire to get her kids to America but just not sure how to make that happen.

(Watch Aramida’s final thoughts about her children's future.)

"A LOST AND FOUND FOR KIDS" CREDITS

Reporter/Writer:Laura Cavanaugh

Producer: Laura Cavanaugh & Shawna Thomas

A.P.: Melanie Roe

Videographer: Brandi Fowler, Will Etling, Shawna Thomas, Laura Cavanaugh

Editor: Laura Cavanaugh

"A MOTHER'S DILEMMA" CREDITS

Reporter/Writer: Shawna Thomas

Producer: Laura Cavanaugh

A.P.: Melanie Roe

Videographers: Will Etling, Brandi Fowler, Laura Cavanaugh, Shawna Thomas

Editor: Shawna Thomas

Print

Print Bookmark

Bookmark