In Their Own Homes, but With a Village to Help

-

Lois Stack planned to be on a plane to Los Angeles in less than 48 hours, for her daughter's baby shower, when her 77-year-old husband slipped on ice, broke one wrist and sprained the other. Stack, 63, felt overwhelmed: If she wanted to make the trip, she'd have to quickly find someone competent and affordable — and trustworthy — to help her husband cook, shower and eat while she was away.

She called Lincoln Park Village, an organization for seniors in her Chicago neighborhood.

The next day, a home-care aide from Relief Medical Services, an agency the village had vetted and recommended, came to her home. Because the Stacks were members, they paid 14 percent less than they would have had they approached the agency themselves.

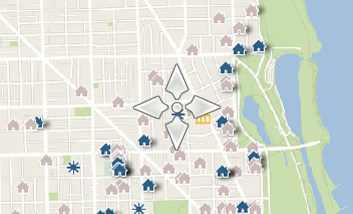

"If I had to start in the phonebook, I would've missed my daughter's ceremony," says Stack. "It was heaven-sent help." Seniors in the Chicago neighborhoods of Lincoln Park, Lakeview and Near North can call the village for whatever they need — a ride to a doctor's appointment, someone to change a light bulb, assistance with Medicare paperwork.

A two-year-old nonprofit serving 230 members in 165 households, Lincoln Park Village was organized by older adults who want to age at home. More than 60 such villages, modeled on Boston's decade-old Beacon Hill Village, have formed across the country, with a hundred more in development.

"Having a support system that can get you the services when and if you need them, but get them at home, seemed to make a lot of sense," says James Zartman, 83, a Lincoln Park founder who has lived in his two-story home for 52 years.

The great majority of older Americans share Zartman's wish to age in place, a 2010 AARP study found. But many are forced out prematurely because they can't fix a leak or drive to the supermarket. For them, the village serves as an all-purpose matchmaker.

Lincoln Park members, who must be over 50, pay an annual fee: $540 for individuals and $780 for a household of two. Those with incomes below $50,000, a fifth of members, belong to the village's member plus program. They pay a reduced rate, as low as $100, and receive a credit toward any expense.

From its small office with two staffers and a clutch of volunteers, the village provides referrals to approved services — home-care agencies, handymen, attorneys, financial managers — that often offer member discounts. The village also collaborates with institutions, like Rush University Medical Center, where members can schedule appointments with specialists or receive counseling.

Help also comes from fellow members and student volunteers. Member Wally Shah routinely drives others to doctor's appointments; a DePaul University student helps a 68-year-old with her unwieldy paperwork; a 50-year-old member and librarian makes "friendly visits" with a retired librarian in her 70s.

"The village is more than just providing services," says executive director Dianne Campbell. "It's beginning to weave a web of relationships and new friendships."

Mary Haughey, 90, for instance, attends the village's tai chi classes, takes walks with volunteers and stuffs envelopes at the village office.

"The village offers my mother stimulation and companionship, and it offers me peace of mind," says Haughey's daughter Michal Brown, who lives an hour away.

-

Across the country, villages have mushroomed primarily in moderate- and upper-income neighborhoods. Most charge an annual fee of $400 to $700, according to the national Village-to-Village Network. If they are to become cost-effective solutions for an aging population, advocates say, they must penetrate more diverse communities.

Questions have also surfaced about the sustainability of villages, which are dependent on donor dollars and membership dues. Founders have been surprised at how difficult it has been to expand membership.

"People say, 'I don't need it now, I'll join it when I do,'" says Lincoln Park co-founder Zartman. "But in the interim, the village will have gone down the tubes because nobody supported it."

Lincoln Park needs 350 households to be sustainable, a daunting target, says its treasurer, Bob Spoerri. Last year, it expanded its potential membership by merging with a struggling village nearby. Meanwhile, even established villages have seen their memberships plateau or drop during the recession. Beacon Hill, for instance, has fallen from 450 to 376 in the last three years.

"Membership money is not enough," says Candace Baldwin of the Village-to-Village Network.

Her organization has begun exploring the possibility of public funding, a tough sell in an economy where "the government doesn't have the money for government," says Joyce Gallagher of Chicago's Agency on Aging. Lincoln Park is mulling whether Chicago villages can share costs — rent, printing, marketing — while maintaining their neighborhood identities, a model currently being followed in Marin County, Calif.

"We'll find a way," vows Campbell. "It's a part of the social fabric, the neighbor-to-neighbor connection that needs to be rebuilt in America."