Siona Benjamin was standing in the back of a small lecture room at the 92nd Street Y on a recent Friday night waiting to give a presentation titled “From East to West: Jewish Indian-Art,” when a woman approached her. The woman wanted to talk about her experiences traveling in India. She told Benjamin she was Jewish and American and that her husband was Hindu and Indian. “Our marriage,” the woman joked “is ‘Om-Shalom.’”

In many ways, “Om-Shalom” would be a good way to describe Siona Benjamin’s lecture—part a discussion of her paintings and part a look into her personal struggle to understand her Jewish identity as both an Indian and as an American.

Her predominantly American Ashkenazi Jewish audience knew a great deal about “Shalom”—the Jewish word for Peace. They knew less about “Om”—the Hindu symbol for the Absolute. And most had never had the chance to see what a Jew from India looks like. According to Benjamin, there are only about 300 living in the U.S. today. Benjamin, who lives in Montclair, N.J., is included in that number.

Benjamin stood behind a small lectern wearing all black, set off by a gold and silver shawl draped over her shoulders and sparkly round gold earrings. Her hair was pulled back off her face and she peered out from behind her black-rimmed glasses with an intense look. “I just wanted to show you some faces, some Jewish Indian faces,” Benjamin said as she began her slide presentation.

For the next half hour some 20 men and women in the audience experienced what was, for most of them, their first glimpse into Jewish-Indian life.

Benjamin started with her upbringing in Mumbai. She is a Bene Israel Jew, she explained, one of three Jewish tribes in India. Her family speaks Marathi, a regional Indian language.

“My parents were staunchly Jewish. They were proud,” said Benjamin. They were especially proud that India had “no anti-Semitism.”

Faces of Indian Jews flashed by on the large screen behind her; black and white posed photos and candid snapshots alike. Many of the Indian Jews she showed looked like average middle class Indians, without any indications of their religion.

When she got to one of her family sitting around the dining room table a hand shot up. “Is that a little Buddha doll?,” asked Dr. Ruth Westheimer, the sex therapist, who chanced upon the talk on a visit to the Y. She was referring to a doll displayed on a counter at the back of the picture. No, said Benjamin. The doll had no religious meaning.

But others photos did have religious significance. She showed a photo of a Jewish Indian bride whose hands were intricately tattooed with henna, a Bene Israeli wedding tradition. “This is one of my favorites,” Benjamin said of the elaborate decoration. She showed pictures of older women making matzah—a traditional Jewish bread made of flour and water. The Indian matzah looked different than Western matzah. It is round-resembling Indian bread — not square. She showed photos of David Sassoon, an Indian Jew who became one of the richest businessman in Bombay in the mid 1800s and who is thought be an ancestor of Vidal Sassoon, the famous name behind the hair product line.

She showed pictures of the ancient synagogue in Cochin, built in 1568, ornately decorated in the Sephardic style and of the Magen Hassidim Synagogue in Mumbai.

Benjamin told the audience that before the creation of Israel there were 30,000 Jews living in India. With just 5,000 Jews remaining, Benjamin said, “very few people can have a minyan (the ten males required by Jewish law for communal prayer) every night.” She added that for her, “it’s almost impossible to have a family reunion,” because so many relatives have left for Israel.

Benjamin also emphasized her constant contact with the two major religions of India—Islam and Hindu—when she was growing up. She said as a child, she was “very close to her Muslim neighbors.” Muslims, she said, were the other “non-idol-worshipping religion” and that put them on common ground.

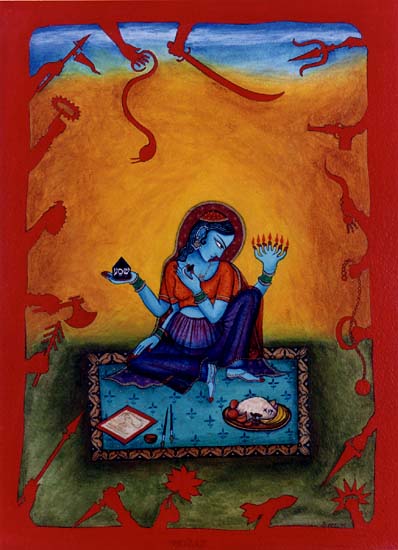

Hindu “idols were beautiful but I eyed them from a far distance. I resisted,” Benjamin told the audience. She said even though she is Jewish she uses idols in her paintings.

“Now, my work is filled with graven images. This ornateness, I carried with me all along,” she added.

In fact, to look at Benjamin’s work, the first impression is Hindu art. Deep red, royal blue, and yellow are common colors in her paintings. Many of the characters she draws look like the Hindu depictions of gods and goddesses, with their long, multiple limbs extending out in all directions. But on closer look, things get more complicated. The body of a woman may be filled in with geometric circles and swirls that are Islamic themed. That same woman may have a yarmulke on her head or Hebrew letters floating above her.

Benjamin admitted to the audience that some people find her art too convoluted to enjoy. One of the only other Indian Jews at the 92nd Street Y, Sam Daniel, said later that in fact some Indian Jews in the New York area are turned off by her work. “It’s a small community,” Daniel said. “They feel threatened” by the dominant Hindu themes, he explained.

But Benjamin, whose likes to use poetry and verse to describe her work or her feelings behind it, emphasized that her contact with so many different worlds gives her special insight into all of them.

“The feeling I have of never being able to set deep roots no matter where I am is unnerving,” she said. “But on the other hand, there is something seductive about the spiritual borderland in which I seem to find myself.”

And on a personal level, she said, she is clear about who she is. “I am a female Jew of color.”

This Glimpse of Faith was filed by News21 Fellow Rebecca Kaufman

Print

Print Bookmark

Bookmark