Rx for an Aging Nation Retirement Money

Late-life Challenges:

What We Lose as We Age

by Abigail Jones, Connor Boals and Scott Sell

For months after her husband of 52 years died last spring, Laurel Frisch struggled to read a book. She couldn’t make decisions; she only occasionally left her house in Rockville, Md. In those rare moments when she could summon the energy, she wandered aimlessly through stores.

“I thought that I had prepared myself for it,” Frisch, who’s 72, says of life as a widow. “Maybe I did, but I’m still feeling devastated. I’m still feeling practically immobile.”

Psychological and emotional losses change the way older Americans live. How they navigate a cascade of challenges — particularly social isolation, widowhood and depression — can determine the course of their final decades.

These struggles often intertwine. Illness compromises independence and mobility. What begins as arthritis, for someone living in a walkup, can lead to social isolation, a cause of depression. Depressed people may grow withdrawn, isolating themselves further. Meanwhile, older adults lose their spouses, partners and friends, sources of companionship, stability and support.

Isolation is a gateway to this cycle of loss. A 2006 University of Chicago study of people aged 50 to 68 documented the dangers: Those measuring higher on loneliness scales had higher blood pressure, for example, a major risk factor for heart disease.

The primary predictor of loneliness in those over 50 is not being married, according to a 2010 study by Laurie Theeke of the West Virginia University School of Nursing. Other contributing factors include disability, increasing illness, and lower education and income levels.

“We have not built a society for aging people,” says Barbara Moscowitz, a senior social worker at the Massachusetts General Hospital. “Feeling a purpose, it’s like oxygen.”

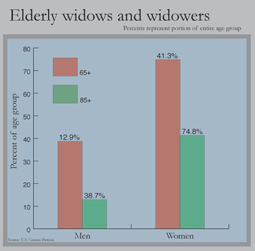

Isolation can be particularly acute for seniors who lose their spouses and partners and live alone. Women far outnumber men in this group. They live longer, often were married to older men who died before them, and are less likely to remarry after a spouse’s death. Last year, 41 percent of American women over 65 were widowed, compared with 13 percent of men, census data show.

Losing a partner affects older adults’ health in several ways, especially if they’re already ill or frail. A couple with health limitations can live independently by relying on each other; when one dies, the other may be ill prepared for new responsibilities and stresses.

Jackie Buttimer, for instance, had never balanced a checkbook and rarely used a computer before her husband of nearly 50 years died in April. “It’s a huge learning curve, and I had never lived alone,” says Buttimer, 71, who lives in Bethesda, Md.

Among older Americans, the death or illness of a spouse increases survivors’ mortality rates, a 2006 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found. A wife’s death increased the husband’s risk of death by 21 percent; a husband’s death raised the wife’s risk by 17 percent. Even a spouse’s hospitalization raises the risk of death, almost as significantly as widowhood.

A surviving partner sometimes finds widowhood freeing, especially after years of exhausting caregiving. The effort can be enough to discourage a woman from pursuing another long-term relationship.

“Some of the women I know who are widows, who have taken care of a spouse, do not want to get married,” explains psychiatrist Carol Nadelson of Harvard Medical School. “They’re worried they’ll have to take care again.”

Frisch still struggles. “I feel like I’m starting almost all over,” she says. “I’ve got my core friends and my family, but I’m alone. It’s different out there being alone.”

Yet while bereaved spouses’ lives change forever, “they adapt over time and arrive at a level of functioning—physically, psychologically, emotionally,” says Michael Caserta, a University of Utah gerontologist and bereavement researcher.

Isolation and widowhood can contribute to the higher rates of depression found in older adults. Among those who live independently, estimates of major depression range from less than one percent to about five percent. They jump to nearly 12 percent in elderly hospital patients, and almost 14 percent in those who need home health care, according to a 2003 study by the Duke University Medical Center. In 2006, the Health and Retirement Study found that 19 percent of those over 85 reported depressive symptoms.

“Elderly populations in this country have less social support than anyone,” explains Amy Fiske, a West Virginia University psychologist. “They’ve often suffered a lifetime of tragic losses, there are economic pressures, and there can be drastic changes in mood as one ages.”

Christopher Lukas, a former television producer from Rockland County, N.Y., hit an all-time low two years ago. He had a history of depression, but between his wife’s death and his own cancer diagnosis, he grew reclusive and distraught.

“I’d wake up in the morning and would think, ‘I just want to die,’” says Lukas, who’s 75. “I was always afraid of getting older and being in pain.” With the help of his therapist, his family, exercise, and various work projects, he has regained stability and purpose.

As Lukas knows, late-life depression is treatable. Psychotherapy and anti-depressants have been shown to improve mood in depressive disorders. Outreach programs use frequent phone calls and home visits to try to mitigate these risks. Still, the stigma of mental illness often makes older adults reluctant to seek help.

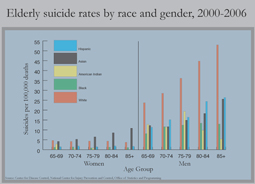

That attitude can be fatal. The suicide rate among the elderly is high: In 2007, it reached 14.3 per 100,000 people, compared to 11.5 among all Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention statistics show that white men over 85 — the “old-old” — had the highest suicide risk.

“Many feel that once they reach the nursing home, their lives are worthless because they’re not able to contribute to society,” says Yeates Conwell, co-director of the Center for the Study and Prevention of Suicide at the University of Rochester.

“Suicide will remain extraordinarily stigmatized among the elderly until we can have a conversation about what needs to be done,” says Briana Mezuk, an epidemiologist at Virginia Commonwealth University.

Increasing public awareness, expanding crisis hotlines, and communicating with religious and community organizations could all help reduce the threat, Mezuk says. Primary care physicians now ask probing questions about a patient’s emotional state during routine checkups. AARP has also taken notice by initiating a series of public education projects. Social workers are starting to use outreach programs, like Meals on Wheels, to screen patients for mental illness. A recent study by the American Dietetic Association found that homebound patients who receive Meals on Wheels have lower rates of depression than those who don’t.

Looking ahead, generational differences could affect such losses. Baby boomers entering their 60s with a legacy of activism and familiarity with technology may well alter the aging experience.

“They are not going to go softly into the night,” says Victoria M. Rizzo of the Columbia University School of Social Work, who has spent decades working with older adults. “These baby boomers are not going to go to the senior center, unless it’s a new breed.”

Mather’s—More Than a Café offers just that: three diner-inspired restaurants that double as community centers for aging Chicagoans, complete with computer and art classes, social events, and health and fitness programs. Mather LifeWays, the nonprofit organization that developed it, has helped replicate the café across the country.

The Internet could serve a similar purpose. Boomers’ Web-savvy ways may give e-mail, instant messaging, and Skype a critical role in increasing social interaction, especially for the homebound.

And boomers may prove more willing than their parents to seek help when life’s losses jeopardize their wellbeing. Frisch is frank about the toll her late husband’s cancer took on her own health. Unlike many older people, however, she sought help after he died, seeing a therapist and returning to exercise.

“I was determined mentally to stay well,” she says. “I’m better off if I am productive, busy and social.”

That’s exactly what Katherine Hinton discovered. She’d cared for her second husband through years of illness until he died in 2005. She mourned, but “I finally caught my breath,” says Hinton, 71, a retired epidemiologist in New York City.

Drawing on her community, her Quaker faith, her work and an innate sense of independence, she has rebuilt a fulfilling life. With her daughter’s family in the same apartment complex and friends nearby, she maintains a busy social schedule. She holds leadership positions in her co-op and other organizations. On weekends, she hikes, and in the fall, she’s traveling to Siberia.

“I’m alone, but I’m not lonely,” Hinton says. “My life is very, very full.” She’s known loss, but “I am OK, I can survive on my own.”

News21 Associate Mary Plummer contributed to this report.

-

Wisdom Begins at the EndA spate of recent research supports one of humanity’s most venerable claims: wisdom comes with old age. Studies identify emotional and cognitive abilities that increase among seniors, including an enhanced ability to resolve conflict and tolerate uncertainty.

World’s Oldest Man Keeps It SimpleThe Guinness Book of World Records has certified 113-year-old Walter Breuning of Great Falls, Montana, as the world’s oldest living man. His secrets are few and simple: two meals a day, light calisthenics and always staying busy.

-

[Click to enlarge this graphic]

Percentage of elderly population that is widowed, by age and sex.

-

[Click to enlarge this graphic]

Suicide rates among the elderly, by age race and gender.

THIS PACKAGE IN DEPTH

To read about how this story came together and the reporters involved

Click Here.

To see this story as published on Washingtonpost.com Click Here