Rx for an Aging Nation Retirement Money

Wisdom Begins at the End:

What We Gain With Old Age

by Josh Tapper

With 14 siblings screaming at each other in a mediation room at the Washington, D.C., Superior Court house, Carolyn Miller Parr started to lose her cool. Parr, the 73-year-old cofounder of Beyond Dispute Associates, a mediation and arbitration practice, was trying to determine who would shoulder responsibility for care of the family’s elderly mother — and the six lawyers present weren’t helping.

A former United States tax court judge, Parr isn’t prone to visible exasperation. This time, though, she yelled back. “See that red button there?” she demanded, pointing to the alarm found in each mediation room. “If I push that, a guard is going to come and if he comes, someone’s going to jail. You can talk one at a time.”

It was an empty threat, but it lowered the temperature, and the family reached a tentative resolution. When they returned for a second session, though, it looked like disagreements would escalate. This time, Parr took a different approach, gently coaxing the adult children to put their mother’s interests above their own squabbles.

“It’s so clear to me that this room is full of pain and anger and hurt,” she told them, as they nodded in agreement. “If you love your mother more than you hate your siblings, you can settle this today.” And they did.

Parr’s pacification — of herself and the situation — was a case study in problem solving: diffuse the situation, temper emotions, then encourage people’s empathy and compassion. “Until you can help them open, to hear what the other person thinks, you can’t settle anything,” she says.

By reappraising the situation and adjusting her emotional response, Parr also illustrates the growing understanding of one of humanity’s more venerable claims: Scientists are coming to believe that wisdom actually does increase with age. “Wisdom begins at the end,” Daniel Webster once said. It looks like he may be right.

Contrary to largely gloomy cultural perceptions, growing old brings some benefits, notably emotional and cognitive stability. Laura Carstensen, a Stanford University social psychologist, calls this the “well-being paradox.” Although adults over 65 face challenges to body and brain, the next two decades of life also bring an abundance of social and emotional knowledge. As social psychologists Carstensen and Fredda Blanchard-Fields, at the Georgia Institute of Technology, have shown, adults gain a toolbox of social and emotional instincts as they age. According to Blanchard-Fields, seniors acquire a “feel,” an enhanced sense of knowing right from wrong, and therefore a way to make sound life decisions.

That may help explain the finding that old age correlates with happiness. A study earlier this year, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, found a U-shaped relationship between happiness and old age, meaning adults are happiest in youth and again in their 70s and early 80s, but least happy in middle age. A 2007 University of Chicago study similarly concluded that rates of happiness — “the degree to which a person evaluates the overall quality of his present life positively” — crept upward from age 65 to 85 and beyond, in both sexes.

Wisdom appears to follow a similar trajectory and not only because raising a family, navigating a career, and experiencing love, loss, success and failure all educate older adults. Researchers caution that life experience is “not a sufficient precondition for wisdom,” says Judith Glück, a psychologist working with the University of Chicago’s Defining Wisdom project.

“Wisdom will only develop if a person is able to reflect upon and learn from an experience,” she says, adding that it need not be someone’s personal experience. “People who are observant, empathetic and reflective may learn a lot from experiences that others around them encounter, even if they are not directly involved themselves.”

What constitutes wisdom? Ipsit Vahia, a geriatric psychiatrist at the University of California, San Diego, says it “involves making decisions that would be to the greater benefit of a larger number of people” and maintaining “an element of pragmatism, not pure idealism. And it would involve some sense of reflection and self-understanding.”

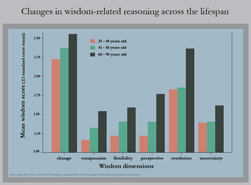

These qualities appear age-related. A recent University of Michigan study on aging and social reasoning tested people in three age groups, the oldest being 60 and over. Presented with a fictional geopolitical conflict, participants specified what they thought would happen and why. Igor Grossmann, a social psychologist and lead researcher on the study, and his team sorted the answers into six categories of “wisdom-related thinking,” including searching for compromise, admitting uncertainty and finding flexibility. The oldest group earned the highest wisdom score in each category.

“Wisdom is the ability to navigate the important challenges of social life,” Grossman says.

In dealing with the warring family, for instance, Parr concedes that any professional mediator worth her salt could have followed her strategy. But she acknowledges a marked change in her own technique as she has aged. “I used to very quickly choose sides when I heard an argument,” she says. Now, “I know I’m much less judgmental of people.”

Whether this development comes from neurobiological or emotional sources is a matter of some debate. If the older brain is hardwired for wise decision-making, science has yet to document that change. An MRI cannot isolate a part of the brain associated with wisdom, says Elkhonon Goldberg, a neuropsychologist and author of “The Wisdom Paradox.” Still, he says, the aging adult has a greater sense of “pattern recognition” — the brain’s ability to capture a range of similar but non-identical information, then extract and piece together common features. That, Goldberg says, “gives some old people a cognitive leg up.”

Others investigating the benefits of old age are more likely to point to social or emotional factors, such as the ability to better regulate emotions, as the underpinning for wiser behavior.

“I never lose control,” says Ambassador John W. McDonald, who at 88 continues to work in international conflict resolution as chair of the Institute for Multi-Track Diplomacy in Arlington, Va. “If you want to do a good job, you have to learn how to control your emotions.”

Older adults have an advantage there. In a 2007 study, Blanchard-Fields and Susanne Scheibe screened a disturbing video for two groups of adults, ages 20–30 and 60–75. All watched a contestant on the reality show “Fear Factor” eating meat identified as horse rectum. They recorded their emotional responses to the scene and then played a memory game. The older age group performed at higher levels, even after reporting negative emotions such as disgust and anger.

Carstensen credits something called “socioemotional selectivity theory”—a focus on positive emotional goals in late life. The elderly tailor their social interactions to increase their well-being; as a result, they make thoughtful, “wise” decisions.

“Old people are good at shaping everyday life to suit their needs,” explains Scheibe. By pruning their social networks or looking at life in relative terms, older adults maintain cognitive control. And although multiple chronic illnesses that cause functional disability or cognitive decline can affect well-being, most older adults are able to tune out negative information into their late 70s and 80s.

“As people age, they don’t have large futures,” says Susan Turk Charles, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine. “So they tend to hang out with really close friends and people who make them happy. Time left in life makes you know what bothers you and what you need to avoid.”

Despite their tantalizing findings, however, researchers still have a nascent and imperfect understanding of wisdom. “One man’s wisdom might not be another man’s wisdom,” Vahia says.

The next phase of research, he and Grossman say, examines whether wisdom can be fostered or heightened. If older adults are predisposed to wisdom, perhaps a graying population means a wiser one.

Parr is satisfied, meanwhile, with her own definition of wisdom. “At first you think wisdom is knowing the answers,” she says. “And then as you get a little older and make a few mistakes in your life, you find out that wisdom is asking questions — and listening to the answers that you hear from other people.”

News21 Associate Mary Plummer contributed to this report.

-

What We Lose as We AgeThe common narrative of aging is loss. A complex cycle of psychological and emotional challenges—social isolation, widowhood, and depression, in particular—can converge to alter the ways older Americans experience their final decades.

World's Oldest Man Keeps It SimpleThe Guinness Book of World Records has certified 113-year-old Walter Breuning of Great Falls, Montana, as the world’s oldest living man. His secrets are few and simple: two meals a day, light calisthenics and always staying busy.

-

[Click to enlarge this graphic]

In this study of intergroup conflict, researchers gave participants three fictional news stories about a geopolitical conflict. Responses were tallied based on six wisdom characteristics. The mean wisdom score combines wise responses – from 1 (“not at all”) to 3 (“a great deal”) – for each of the three stories.

THIS PACKAGE IN DEPTH

To read about how this story came together and the reporters involved

Click Here.

To see this story as published on Washingtonpost.com Click Here